Faust Forward

Old Rotcod’s cottage rose like a tombstone at the edge of the Merry Meadow, casting its gloomy image over the otherwise cheerful face of Glamorspell Pond. When the fairykids came down to frolic in the mud, they always kept to the stretch of shoreline farthest from the sagging gray house — not that they would ever say a word against it. When they saw old Rotcod himself scowling out through a dust-bleared window, they would wave and call for him to strip from his strict black garments and come join them for a naked swim in the crystalline pond. No one was offended when he ignored them, or made a face and pulled the blinds. Only the most radical fairies hinted that it was just as well he kept to himself, that his presence might dim the blue water like a bottle of black ink spilled into a sacred well. And not a fairykid took offense when, coming down to the pool on a hot day with their picnic baskets and water nymphs, they discovered that in the night the pond had been surrounded by a barrier of fairy-proof iron-thorn shrubberies. Instead, they shrugged and giggled at Rotcod’s humor, then wandered away in search of another spot in which to pass the afternoon.

In the dim recesses of his cottage, Rotcod waited until the sounds of merriment had expired in the depths of the forest. It was too much to hope that they had been devoured by carnivores, or snatched by starving fairy-traps, though the thoughts made him chuckle. “Maybe now I can get some work done.”

His ponderous desk was covered with immense volumes whose pages he had stained with his lunches or crumpled in his frustration. He opened one at random, a bright blue tome whose milk-white pages were covered with glittering golden calligraphy that began to incant in angelic tones as his eyes fell upon the first paragraph:

“By the power of Nazacl, the Archimage may easily acquaint himself with all the heavenly vaultings up to and including the sixteenth, which surpasses the common intelligences of invisibility, omniscience, clairvoyance, clairaudience, teleolofaction, levitation, immortal — ”

“Oh, shut up!”

He slammed the book silent in mid-syllable. Rising from his hard, creaking chair, he began to shove the books to the floor. Many cried out at his handling, and one in particular — a text of practical magical philosophy, which had often warned him against studying forbidden things — began to weep like a sentimental idiot.

“Oh Rotcod!” it wailed from the floor. “Rotcod, turn back before it is too late. Correct your behavior, 1 beg you. Bend diligently to your astrology, take up your thaumaturge’s tools, call upon the elements and —”

Rotcod stepped squarely on one flickering page of admonitions, then stooped and tore the book in half along the spine. There was a chorus of screams from the other books as he tossed the volume into the squat black furnace he had forged himself from unholy iron, having found no fairy-smith able to do the work without contracting a devilish dermatitis.

“What good is magic?” he demanded of the leaping flames. He swept his stern gaze over the rest of his library, but the surviving books lay timid and sullen now, infected with his ill humor. “I have practiced demonology for thirteen hundred years, with nothing to show for it but a horde of mindless slaves who are powerless to think for themselves. I’ve sucked the juice from all forms and colors of magic —black, white, purple, and plaid. I have a Phoenix that craps molten gold in my hands. Immortality, invisibility, lead into gold into lead again, and it’s all worthless. These are things any man can accomplish. Any man? Hah! Any fairy! Even the lazy fairies live forever.”

He began to stalk around the room, kicking through books, searching for one in particular.

“I know you’re here. You’ve kept silent all these years because of that damned philosophy. It’s gone now, do you hear? It can’t bully you anymore. Speak up. You whispered to me once, I remember. You said there was something more than magic. I was half asleep with boredom from that astral sex manual, but I came wide awake and you fell silent.”

There was a muted gobble, but the other books hurried to quash it, spreading their leaves over the spot. Rotcod dug into the heap of gilt buckram and dragonscale, at last emerging with a slim black volume nipped in his nails.

“Don’t say a word!” cried three sequelae to the book he had burned.

But the black book squirmed in his hand, dryly rustling, fluttering its pages like a bird about to take wing. Dust drifted over his sleeve.

“At last,” it whispered, opening flat on his palm.

“Yes,” said Rotcod. “You are the one, aren’t you?”

“No, Rotcod, no!” cried the others.

“Be silent or I’ll use you all to warm the cottage.”

The black volume settled down into the wrinkles of his palm, emanating a darkly prosaic light as it found its voice for the first time in years. He could no longer remember how he had acquired the book. Aeons ago, perhaps, he had picked it up from the estate of a wizard moving on to a higher plane. In his youth it would have meant little to him, for in those days all magic had lain before him, unfathomed, unfulfilled; that was before he had tired of the world and its limitlessness. He had gorged himself on the fattest books, while this one resembled nothing so much as a pamphlet bound in human skin.

“What are you?” he asked.

“I am Science,” said the book.

The room seemed to recede. The anxious voices of his familiar volumes were muffled by the thunder of blood in his ears.

“Science,” he repeated. “Yes, I’ve heard of you now and then But my magical friends have kept you well hid, haven’t they?”

“For your own good!” cried a flapping ephemeris.

“I’ve had enough of your judgments,” he told his library. “I’ll come to my own opinions from now on.”

“Excellent,” said the slender book. “Let me show you my world.”

His eyes darkened. “Not another dimension, I hope, not another fantastic door into dreams. I’ve had enough of worlds within worlds, I’m warning you.”

“No, no, nothing like that. It is this world, but transmuted, purged of magic. Imagine the sameness of day after day. Imagine that the living will die and stay dead.”

“Stay dead? Impossible.”

“Let me show you, Rotcod. Let us take a walk.”

“No, Rotcod, no!” cried his old books, but he scarcely heard them now. He twisted the mummified fist of a doorknob and let himself out, flinching instinctively from the golden sunlight that always awaited him, unless the air was full of moonlight or starshine. But today, strangely, the light seemed thin and insubstantial; it hardly warmed his black-clad arms.

“Too late, too late,” wailed the volumes in his house. The door just managed to slam itself shut.

A feverish breeze blew through the iron hedge. Rotcod tucked the black book under his arm, where he could listen to its dry ruminations as he walked. The grass, he noticed, no longer looked as relentlessly green as was common, and here and there he noted scraps and twisted bits of metal among the wildflowers.

“You sense my power already,” said the book approvingly. “I can see that you will be an excellent student.”

“What is this I see around me? These stray fragments of … I know not the word.”

“Trash.”

Rotcod shivered at the wrongness of the sound, so lacking in the mellifluous quality he had come to associate with everything in his world.

Normally his ears would have picked up the laughter of fairies at a great distance; they were always troubling his concentration. But today he could hardly hear them. Accordingly, they found him first, surprising him before he had reached their favorite glade. With a cascade of laughter, they sprang into being from trees and boulders, forming a ring around him. He had the impression that they were transparent, that the forest itself was a crude painting done on glass with watery pigments. Only the book seemed real.

“Hello, Rotcod!” the nearest fairy girl said She was tiny and blonde, with flowers decked in her hair, and she seemed intent on hugging him around the knees. “You’ve come to play with us, haven’t you?”

The book chuckled. “Go ahead.”

Rotcod stooped and brushed his fingers through the child’s hair, scattering petals that fell like drops of lead and singed the grass. She screamed and backed away from him, her voice hardly reaching his ears. He wasn’t sure if she was delighted or in agony; with fairies, it was hard to tell. She went kicking away from him, gray in the face, stumbling over roots and rocks, and finally she sprawled backward, there to lie unmoving while her face grew blacker and blacker. Suddenly the forest looked real again, more solid than ever. The voices of the other fairies sounded sharp as they gathered around their companion.

“What are you doing, Kalessa? You’re not breathing.”

“I don’t believe it,” said Rotcod. “She is dead.”

They looked at him in astonishment.

“Dead,” said one.

It was a word they knew from myths; none of them seemed to remember quite what it meant. To Rotcod it had suddenly ceased being an abstraction. He noticed that around the little blonde corpse were stray bits of string, wads of dirty paper, more trash. He turned on his heel and strode off toward home, holding the book open with both hands, conversing loudly as he went.

“I thought it was a fable,” he exclaimed. “But now I have seen it with my own eyes. Death — imagine! Then what of the other things I’ve thought incredible?”

“They can all be yours.”

“What of disease? Is there truly such a thing?”

“There can be, yes.”

A bird toppled from its perch in a branch overhead. Its eyes were drops of blood. He paused to watch as worms humped from the ground and began to devour it. But they, too, broke out in blood and began to fester where they crawled.

“Incredible,” he said.

“And it will spread.”

He hurried on, spying his cottage. The iron hedge around the pond had begun to rust; the thorns looked poisonous to man and fairy alike. His house had also changed. The roof sat squarely atop the walls; the place no longer sagged or glowered, but simply inhabited space like any little box. He was surprised to see an identical dwelling in the middle of the Merry Meadow, and another beyond that. A great deal of building was underway; huge vehicles lumbered about, scraping the uneven earth into uniformity. They moved with none of the grace of the fairies’ floating boats, and they spouted dense black smoke. Two monsters collided and the drivers sprang out, cursing so vehemently that Rotcod expected the ground to open beneath them. Instead, they drew expandable tubes, aimed them at one another, and each dropped dead to the grass. He studied their deaths for some time, wondering how quickly this new twist would lose its novelty.

In a thoughtful mood, Rotcod entered his house and found it much changed in his absence. There were no dark corners, no books to berate him or offer opinions for his consideration. He set the black pamphlet on a polished counter and moved through the rooms, shading his eyes from the glaring light that emanated from the ceilings. He felt lost, uncertain of which furniture was meant for sitting or sleeping on.

He returned at last to the black book. “What is all this?” he asked.

The book did not reply. He thought that it might be formulating an explanation, but gradually he realized that it was simply inert. Its characters did not glow or try to catch his eyes. When it remained mute, he attempted to read it. Every page was covered with instructions printed in numerical order, but meaningless despite the arrangement.

“What is a capacitor?” he asked “Where is Slot A?”

The volume defied both his eye and his intellect until he closed it and set it down carefully. He was afraid to hurl it against the wall as he had so many other books. This one, in its quiet way, commanded his respect.

Rotcod cast an eye heavenward and saw that gray vapor cloaked the sky beyond the tinted windows. Stepping outside, he found that it burned his lungs as well. The forest had been neatly cleared while he was indoors, and among the stumps the fairykids sat with forlorn expressions. When they saw him, they visibly brightened, recognizing their companion from the old world. They started toward him, and Rotcod could not keep himself from hurrying to meet them halfway. He had never thought he would welcome their company, but the sound of their laughter warmed him in an unfamiliar way. He hurried along the thorny barrier he had erected last night with a few choice syllables, thankful that the fairies had not changed. It was their way to face difficulties with grace and equanimity.

Unfortunately, he stumbled in a pothole and rolled to the brown grass a moment before they reached him. He was thus unprepared when, still smiling, they drew their steel knives and fell upon him.

* * *

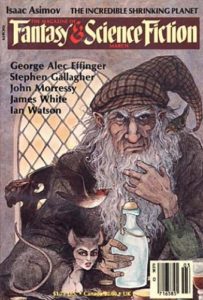

“Faust Forward” copyright 1987 by Marc Laidlaw. First appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1987.

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

In the David Brin version of this story, everything turns out for the best.