Sweetmeats

Hugh bit his lip. He did not cry out, both because he feared to show fear before the hungry gumball eye, and because he felt no pain.

The King of the Mbe’lmbe stepped forward with Hugh’s fingertip extended. Hugh looked at that and not his hand. He saw a round pink stub with a soft moonshell of fingernail, still quivering, still unaware it was no longer part of him.

The old Master took the offering and held it up to the fierce oven light, regarding it from all sides, uncertain. He gave the little King a most curious questioning look, to which the King responded with a firm nod.

The old man licked his lips with a dry grey tongue, then popped Hugh’s fingertip into his mouth.

Hugh gasped as if feeling the old man’s rotten teeth in his flesh.

The old Master shut his eyes. He bit down once, and Hugh heard a brittle crunching. He bit down twice, and Hugh heard the juices squirting. The Master’s eyes opened, rapt and delirious, delighted, a broad smile spreading over his face, transforming it in an instant into the face of very old and wizened child.

“My God!” he crowed. He rolled his eyes.

“I tried to tell you, Master,” said the King.

The old man rushed toward Hugh and caught him up beneath his arms—caught him and threw him high into the air. He felt the furnace breathing over him, felt it might gape and swallow him whole.

“Yes, that taste, that wonderful taste…it comes back to me! Oh, sweet victory! Oh, ecstatic sweetness, sacre sucre! The taste of sunlight to the leaf! My boy, my dear boy, what a terrible misunderstanding! Oh happy day! Oh joy to you, joy to us all!”

He set Hugh down, and patted him tenderly on the head. “But…do you not see, my boy?”

He fluttered the golden bookmark, and on it Hugh saw scratches of writing, thin letters incised in the foil and glinting. The lines were short and broken, like lines of poetry, like something else. Like…like…

“The recipe!”

“For what?” Hugh asked.

“When I first drew you from the oven, ah, so small…” He held his fingers to show a mere pinch of boy. “So pink! Yes, yes! Dusted in pink sugar, my marzipan boy…so warm and fresh and sweet, with the raspberry coursing through you. Why, I could have eaten you whole!”

The old confectioner’s eyes gaped, bulged, oozed sugary tears, staring at something beyond.

“Come with me, my boy. Come now…this way…while the mood is upon me, while change is in the air, quickly now, quickly!”

Hugh realized, as the old man’s hands led him firmly along, that the glazed eye was fixed on the enormous oven. Above them burned an orange sun of flame, bright enough to have lit this and a hundred other underworlds; but that was the top of the chimney. At floor level, coming closer, was the door of the oven.

“This way! This way! Right along here! Your heritage, my boy…your birthright, and your birthing place. Exactly as intended, yes, I remember it now. Exactly! You were to take this burden from me when I was too weary to carry it. You were to be raised at my side to continue my work, taught from my books, fed from my fingers… And look what time it is! We must be quick, lad, quick!”

They paused at the gate of the immense furnace. Thick glass barely held back the volcanic fires within. Intense heat caused the oven door to bulge and blister toward them. The old confectioner reached out to twist a silver knob, and just like that the flames died down to nothing, and went out.

“Here, lad, have no fear! It’s completely cool! Put your hand upon it!”

Hugh put out his hand and touched the glass. The furnace roar was less than a whisper, and the heat had died down completely. The flame still burned somewhere in the heights, but down here it was cool.

“You will learn such secrets now, the mysteries of the oven will be yours…come up, come up!”

The oven door drew up like the portcullis of a castle. He reached unbelieving into the cool interior, black walls speckled with grey, long racks that seemed to continue for miles back into darkness, the mouth of a spotless cave…

And suddenly the hand in his back pushed firmly. He lost his balance, tipped and plunged. The King of the Mbe’lmbe shrieked and reached out for him, but they were both lost in that instant. Hugh fell hard on the spotless floor. As he felt the King’s hands on his arms, trying to pull him back, he heard the whirr of oiled hinges and the deafening boom of the oven door sealing shut.

He rose and turned. The King lay weeping on the ground, crumpled by failure and betrayal. Hugh could see the old confectioner, a shadow beyond the tinted glass, something made of smoke. The old man raised his hand to the silver knob by the side of the oven door. Then the glass began to fill with light. It felt to Hugh as if the sun were rising at his back.

He scarcely minded. It was a pleasant warmth, something familiar and almost comforting about it, as if he might melt away with a smile upon his face.

But it was otherwise for the King of the Mbe’lmbe. Hugh only slowly realized what he was hearing, and what it meant.

The little man was screaming.

He turned and hammered his fist on the glass, making a rhythmic pounding to which the twisted figure beyond the glass seemed to dance an antic jig. He was certain he saw the top-hat tossed high into the air and caught again. The old man was dancing out there.

“Please!” he cried. “Please help! Please, somebody, help him! ”

His hands left sticky bubbles on the tempered glass. He could hear the sizzling of flesh behind him, then came a burning smell unlike any that oven had ever known or should have known. Flesh…

Beyond the glowing pane, something greater moved. A spot of darkness swiftly expanded and swelled, glistening, gleaming, becoming immense. Against it, the small shape of the old confectioner stiffened, grew tense, began to back away. The old man retreated until he was pressed against the glass of the oven door, separated only by that thin hot sheet from Hugh’s clawing fingertips. The old man turned to the glass, his face directly opposite Hugh’s, but all unseeing, blind with fear. Then the old face went awash in blackness, smothered in it. A gluey brown wave drenched the glass, washing over it like a thick and sticky tide that eventually, reluctantly, subsided. In drawing back, it flailed decisively at the silver knob, and the flames abruptly died.

The oven door hissed and opened slightly. Hugh stumbled forward, then stopped and turned back to find the King limping toward him, his hair singed and smoking, his skin a mass of developing blisters.

Together they stared across the sticky waste.

The floor was like the shore of a sea of molasses at low tide. A crumpled top hat floated in the middle of the flood. There was no other sign of the old confectioner.

The doorway to the Sweteshoppe swung ajar, and slowly came to rest.

The King croaked in an urgent hush: “My farewell to you, young master. The sugarbirds again will sing in the rafters, but I will not linger here to hear them. I will not allow myself to come to hate you as I grew to hate him. I have sung my death song already. I go to lay myself among my people.”

The sadness of the King’s words overwhelmed him and Hugh began to weep. Great sugary tears rolled down his cheeks and he flicked them aside with his tongue, trying to take no pleasure in so doing. The King of the Mbe’lmbe, last of his kind, clasped his hand with finality, then turned and walked over the Sweteshoppe threshold. Within, a great darkness gleamed as if welcoming the King. Then the door shut and Hugh was alone.

Absently, he put his severed finger in his mouth and began to suck.

And sucking, tasted sugary sweetness, raspberry jam, a touch of caramel, and the almond softness of marzipan.

Sugar.

The stuff of life.

The taste of sunlight to a leaf.

If a mere man, with all his indigestible impurities, had whipped up such sweet life as he from scratch, then what might he, a boy of sugar, dream of making? What radiant creatures of unsullied sweetness might issue from that titanic oven and soar out to dust the world with powder from their wings?

With visions overwhelming him almost to bursting, he realized he was nibbling the very slightest bit from his finger.

He forced himself to stop, although it was difficult.

No more! He must find other sources of nourishment. He must make himself last as long as possible.

It would be a struggle, a constant temptation.

After all, he was so incredibly sweet.

* * *

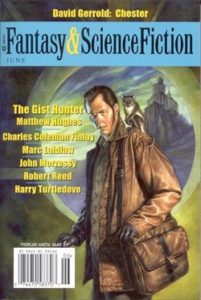

“Sweetmeats” copyright 2005 by Marc Laidlaw. First appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June 2005.

AUTHOR’S AFTERWORD:

Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory might have been the first book that made me want to be a writer. But while I spent my teens imitating my later favorites, writing countless Lovecraft pastiches, I never really dared to try honoring my first literary idol until much later. “Sweetmeats” is something along the lines of an unauthorized sequel, an attempt to spend some quality time in the Chocolate Factory. It had occurred to me that although that novel ended with good fortune for Charlie Bucket and his family, the long-term prognosis was not necessarily bright. Did Charlie display the slightest genius for invention, any innovative streak, any predisposition at all for inventing new delights? It seemed to me that the only thing he had done to distinguish himself from the other Golden Ticket winners was…nothing. His qualifications were primarily negative ones. He refrained from causing trouble. He took no risks. That’s not exactly the quality, the mad flair you’d want in your lead chocolatier, is it? And now that job, which he hadn’t even known he was applying for, is to be his forever. It seemed like a heavy responsibility, one that might over the long years take a toll.