The Demonstration

As they approached the site of the company picnic, Dewey and his parents saw a crowd of weird-looking people standing along the roadside waving picket signs. Dewey’s father muttered, “God damn” under his breath.

“Roll up your window, Dewey,” said his mother.

“Who are they?” Dewey asked, putting up the rear window of the station wagon.

“Anarchists,” his father said. “They’d like to see us all turned into animals — and worse.”

Animals? Dewey wondered. He got up on his knees to see them better. By now the car had slowed to a crawl. Dewey’s father sounded the horn. “Get out of the road!” he shouted, though his voice didn’t carry with the windows all rolled up.

“Daddy, why do they want us to be animals?”

“It’s a figure of speech,” Mommy said.

But the anarchists looked halfway to animal already, like the creatures of Dr. Moreau. They wore their hair long and ragged; their cheeks were slashed with black-and-white zebra stripes, their eyes wild and beseeching. Some of them looked like living skeletons, zombies in tattered clothes.

“There’s a spy in the company,” Daddy said suddenly.

“That’s ridiculous,” Mommy said.

“How else could they have learned about the picnic? They’re trying to spoil everything — first the Project and now our private lives. God damn them!”

“They have their own beliefs. They’re concerned citizens.”

“They don’t give a damn about civilization.”

The skulls and animals lurched toward the car, spilling onto the road now. Dewey jerked back as a woman with long claws raked the window an inch from his face. She screamed into his eyes: “Make them stop! It’s your generation that loses! Your own father is killing you!”

Dewey felt his insides turn cold. “Mommy…”

“Don’t listen to them, sugar.”

The horn blared, and the station wagon sped up. The woman stumbled away, losing hold of her picket sign. Dewey read it as it fell: BRING BACK THE NUKES!

Just ahead was the private gate, standing tall between high bushes. Guards waited there with hands on their holsters. The crowd stayed back on the main road, still shouting and waving signs. The guards stepped aside and let the car pass through, nodding in recognition to Dewey’s father. The station wagon rushed down a dusty road between summer-browned oaks, dry-baked hills.

“Daddy,” Dewey said, “what’s a nuke?”

“You don’t need to know,” his father said. “They’ll soon be obsolete.”

As they pulled into the small parking lot among fifty other cars, Dewey saw that the barbecue pits were already smoking and a softball game was under way. Plenty of kids were playing around the picnic tables, but he didn’t know any of them. This was the first company picnic since Dewey’s father had come to help supervise the Project. There hadn’t been time to relax until recently. Daddy was always griping about deadlines. But now the Project was finished. The new power station had been in operation for a week, running smoothly in the nearby hills. At last the company had granted its employees an afternoon to picnic with their families.

While his parents unpacked the station wagon, Dewey wandered toward a small group of kids who were kicking a soccer ball between them. He stood at the edge of the game for a few minutes, trying to figure out if there were any rules—until someone kicked the ball too hard, and it flew past Dewey into the heavy underbrush that surrounded the picnic grounds.

Dewey shouted, “I’ll get it!”

He plunged into the tangled brambles, thinking that if he retrieved the ball, he could make some friends. The others shouted encouragement as he stooped ever lower; soon he was almost crawling. Then, just ahead of him, he saw the ball. He ignored the thorns that scratched at his face and arms, and pressed forward.

A black hand darted out of the thicket and grabbed at his wrist.

“Hey!” he shouted, tearing himself away.

Something moved inside the hedge, struggling after him. Whoever or whatever it was grew trapped in thorns; the hand fell out of sight. He stumbled backward, terrified. A black hand! It hadn’t been the chocolate brown of his own skin; no, it had been the black of something badly burned.

A second later Dewey was free of the bushes. The other kids were waiting for him. “Well, where is it?” asked a tall blond boy.

Dewey couldn’t catch his breath. “There’s someone in there,” he gasped.

“Someone stole our ball, you mean?” said a girl.

He looked back at the bushes, but they were silent, unrustling.

“Naw,” said the blond boy, “he’s just chicken.”

“He does look scared,” said another kid.

“You go get it, then!” Dewey said angrily, turning away from them so that his fear would be hidden. He decided that he didn’t want to play with them after all. He walked slowly past the picnic table where his mother was setting out plastic bowls full of salad. His father was standing with a few other men, all of them drinking beer in the shade of an old oak tree. Dewey went up to them and waited for his father to notice him.

“Daddy,” he said, when the men kept on talking. “Daddy, there’s someone in the bushes over there.” He pointed, but now saw that the kids had their ball back and were kicking it across the dry grass.

“What’re you talking about?” his father asked.

Dewey stared at the motionless thicket; there wasn’t even a breeze to stir the branches. Suddenly he remembered the people on the road.

“Those animal people,” he said.

That got his father’s attention. “What do you mean? The anarchists?”

One of the other men laughed. “Those idiots. How did they ever get it into their head that the Project was dangerous?”

“I saw one of them, Daddy. He was —”

“Where?” Dewey’s father whirled around, searching the hills, the hedges, the trees. “You saw them, Dewey?”

“Relax, man,” said one of the others. “They can’t get in here.”

“You don’t know that,” said Dewey’s father. “Those people won’t stop at protest. They don’t respect normal people. I carry a gun now; you’d be crazy not to.”

“Come on, who’s going to resort to violence over a little thing like a power plant? It’s for their own good, even if they don’t understand how it works. They’re ignorant, that’s all. Superstitious. If they really understood tau particles and time/mass transfer, they wouldn’t be afraid anymore.”

“Believe what you want,” said Dewey’s father, still eyeing the landscape with suspicion. “You remember how violent the antinuke protests got; or have you forgotten already?’

“Yeah, but that stuff was dangerous. This is safe.”

“You can believe that if you want, too,” said Dewey’s father.

“I gotta say,” said another man, “they did give me a bit of a scare on the way in. You saw how they were dressed. Kind of reminded me of the nuke protests, the dead-falls. Remember when the protestors used to dress like burned-up corpses and skeletons and fall down dead in the streets?”

“That’s what I saw!” Dewey shouted. “Just like that! Down there in the hedge!” He pointed again.

The men laughed among each other, all except Dewey’s father.

“Kid’s got quite an imagination.”

“Dewey doesn’t imagine things,” his father said.

“I’m telling you, those demonstrators can’t get in here. Don’t let them ruin your day.”

“They already have. Come on, Dewey.”

Daddy started back toward the car. As they passed the picnic table, Dewey’s mother looked up and saw the expression on her husband’s face. “Honey? What is it?”

He didn’t answer, except to glance sideways at Dewey and say, “Get in the car.”

“Why, Daddy?”

“Don’t argue, just get in the car.”

Dewey slid into the backseat while his father opened the front door and reached under the seat. He straightened and quickly tucked something into his belt; before the shirt covered it, Dewey saw the handle of a gun.

“Daddy?”

“Keep still. I saw something in those bushes, too. More than one. I think we’re surrounded, Dewey; that’s why I want you to stay in the car. The rest of these fools won’t believe me until it’s too late. Now I’m going to try and get your mother to come sit with you if I can do it without scaring her. Then we’re going to drive out of here the way we came in.”

“But Daddy, the picnic—”

“Keep quiet, I said. The picnic doesn’t matter.”

Dewey’s father slammed the door and went striding toward the picnic table. He took hold of Mommy’s arm and began to whisper urgently in her ear. Dewey saw her look change from concern to fear and then to irritation. She was about to argue, when a scream caused everyone to turn.

One of the girls playing kickball was standing in the middle of the grass, pointing up at the hills. Dewey saw a black figure come stumbling down through the bushes, a weird man dressed in rags. And he wasn’t the only one, either. All of a sudden the hedges and hills were dotted with terrible-looking people; they came staggering toward the picnic tables, pushing through the bushes, howling and scraping at the air. They had left their picket signs behind, demonstrating their protest now with actions instead of words.

The company picnickers moved back toward the car. A woman ran out into the field and grabbed the screaming girl. Panic broke out among the tables. Dewey’s father pushed his mother toward the car, and she came running willingly now, her eyes wide with terror. Daddy drew his gun and aimed it at the nearest target. A small black shape broke free of the hedges where Dewey had sought the soccer ball. It reminded Dewey of a spider, a charred spider with half its legs pulled off. The sound it made was a horrible, senseless wailing. It lunged at Dewey’s father, and he fired without hesitation.

The black thing fell dead on the weeds. The gun sounded again and again. By now the other men were running for the cars, pushing their families inside; a few pulled out shotguns they carried mounted behind the seats. With loud whoops, they rushed out to join Dewey’s father. The protestors kept on coming, and the killing began in earnest. The long grass hid the bodies as they fell.

“Come back here!” Dewey’s mother screamed from the car. “Come back here right now, damn it!”

Dewey’s father hesitated, glanced back at her, then lowered his arm. He ran across the field and jumped into the car. “Out of bullets anyway,” he said as he started the motor. Dewey’s neck snapped as the car leaped backward, screeching out of the parking space. The station wagon lurched forward in a sharp turn, and then they were speeding along the narrow road.

At a blind turn, a car shot out in front of them. Dewey’s mother screamed; the brakes squealed. The cars collided with a soft metallic crunch and the shattering of glass.

After that, Dewey lay dozing in the seat, aware of the stillness of the hills, the soft sound of settling dust, the warmth of the sun. He thought it was the most beautiful moment he had ever known. Then he remembered what had happened, where he was.

He sat up and saw Daddy standing on the road talking to another man, the driver of the other car. Mommy leaned against the hood, holding her forehead. As in a dream, Dewey opened his door and walked toward them. Everything seemed to speed up; it felt as if the world were beginning, ever so slowly, to spin like a carousel. He was dizzy and sick to his stomach.

“What the hell are you doing here?” Dewey’s father asked the man.

“What do you mean? I came for the picnic.”

“The hell you did! You’re on duty this afternoon — you’re supposed to be watching the board.”

“Not me,” said the man angrily. “I swapped with McNally. He’s watching the board. We made a deal.”

“I just left McNally in the picnic grounds. He’s back there taking care of some demonstrators.”

“The ones at the gate?”

“That doesn’t matter. What matters is that your butt is in the wrong damn place. You’re not supposed to deal with McNally; you deal with me.”

The man shook his head, staring at the broken noses of the cars. “Shit. You mean McNally’s here? Then who’s at the board?”

“That’s what I’m asking you!”

The other man shrugged, avoiding the eyes of Dewey’s father.

Just then Dewey’s nausea surged. He didn’t have time to ask his mother for help. He ran to the side of the road, bent over in the bushes, and began to vomit.

Everything went dark. The carousel was spinning full tilt. Dewey sprawled over in the dirt, crying wordlessly for his parents. Thorns tore at his face; the sun scorched his arms, and his lungs filled with dust that tasted like smoke and ashes. He thought he was going to faint; he saw his father’s hand reaching to pull him to his feet. He grabbed hold of Daddy’s wrist for the merest second, then lost it. The world got even darker.

Dewey’s dream seemed to last an eternity. He saw bits and pieces of his whole life, strewn together and flying about in a feverish whirlwind. For a time he lay comfortably on the backseat of the station wagon, wrapped up in a blanket and listening to his parents talk while streetlights flickered past. Then he was at his grandparents’ house, playing with their old dog, the one with cataracts who peed every time the doorbell rang. He was climbing the tree behind his house, eating fresh corn, smelling the dusty electric smell of rain and thunder that came with a storm.

And then he woke up, still burning with fever. He must have wandered off the road farther than he thought, deeper into the bushes. He could hear voices, someone shouting. He crawled toward the sound, wanting only to be safe with his parents, away from the animal people, the zombies, the gunshots, the bodies, away from the accident and the thorns. He got to his feet in the bushes, and suddenly he was out in the open; he was free.

He tried to suck in a deep breath, but it hurt his lungs. He blinked away harsh tears and sunlight. Then he saw Daddy.

Dewey wailed with relief and started running. “Daddy!” he cried, though his throat was still sore and the words didn’t seem right.

In fact, nothing seemed right. He had come all the way back to the picnic grounds. There were the tables; there were the cars; there was Mommy running away.

And here was Daddy, aiming his gun. Aiming it right at Dewey and squeezing the trigger.

* * *

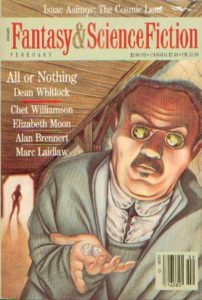

“The Demonstration” copyright 1989 by Marc Laidlaw. First appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1989.

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

Nothing dates quite as badly as a time travel story.